004: 2 Frozen, 2 Furious

On seasonal depression and the end of the world

The paranoid are correct: the universe is out to get us. You and I are situated on a pretty rock traveling through space at 60,000 miles per hour, and at any moment, over 100 million asteroids are crossing our path of orbit. If one were to meet us at the right place and time, we likely wouldn’t know until a second before impact, and that’s if we happened to be awake and positioned by a window. Upon impact, the air beneath the asteroid would heat to a temperature 10,000 times hotter than the Sun and instantly eviscerate everything within 150 miles of the impact zone. If this were to happen in, say, the tiny town of Manson, Iowa, as it did 2.5 million years ago, everything from Denver to Detroit would be flattened or on fire, and debris would dice anyone in a thousand-mile radius like tomatoes. The rest of the world would face a chain of volcanoes, earthquakes, tsunamis, instant and extreme shifts in climate, the release of noxious gasses, and a total loss of communication to anyone outside of yelling distance.

Earth doesn’t seem to want us here either, or at least not this many of us. Roughly 99.5% of Earth (by volume) is uninhabitable by humans. We are land creatures, and only 30% of Earth’s surface is above water, much of it belonging to enormous glacial masses at the north and south poles which are too cold to inhabit and, due to our irresponsibility, are rapidly melting, further increasing sea levels and submerging areas of land where we could otherwise settle. By the end of the century, creeping ocean waters will create a climate refugee crisis on every continent north of Antarctica. In the U.S., Miami will be the first city underwater, which is something of a silver lining.

But thank goodness for the land we do have, right? Well, I hate to tell you that most of it could blow at any moment. There are roughly 1,500 active volcanoes around the world — probably more, considering humans figured out how to fly before they discovered Earth’s core and that Skip Bayless makes more accurate predictions than the world’s most respected volcanologists. We refer to the largest of these volcanoes as Yellowstone National Park, a 2.2 million-acre caldera that usually erupts every 600,000 years. The last time it erupted? Roughly 630,000 years ago. A Yellowstone eruption would likely be 300-1000 times more powerful than the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980, meaning everyone within 600 miles would immediately die and the rest of the continent would be covered by hundreds of feet of ash until the survivors removed it — and that’s if it failed to trigger plate movement or other volcanoes. Breathing, much less growing food and finding clean water sources, would be nearly impossible.

I could continue on about the countless and ever-present threats to humankind — global pandemics (ugh), bacterial evolution, atmospheric shifts, white dudes with guns — but it would likely take an afternoon. It took Bill Bryson almost 500 pages in A Short History of Nearly Everything, from where this information comes. Plus, it’s a Tuesday morning and some of you probably haven’t had your coffee yet.

So I’ll talk about the other thing I mentioned in the subtitle of this Garbage — a thing that, when I read Bryson’s book, made me feel not sadness or panic or the urge to loot things from my local Best Buy, but, strangely enough, relief.

Around this time every year, when temperatures drop and sidewalks become slick with dirty slush, I devolve into a lethargic and unmotivated creature that wants nothing but to hide away in bed until springtime. Since I was a kid, I’ve struggled through the months of January-March. My toes are always cold, it’s dark for more than half the day, and I’m convinced that nothing good will ever happen to me again. Last week, gloomy clouds dominated the sky for four consecutive days and I took to drifting my car around my icy parking lot like Paul Walker, e-brake and all, just to feel something. However, my driver-side tire is now making a grinding noise when I turn left, which is proof to me that any attempt at happiness will have an equal and opposite effect.

Like my Kia Forte is at the mercy of even the smallest patch of ice, my mood is at the mercy of my environment, and in the winter, when I need shelter from that environment, my world shrinks to a claustrophobic size. Thus, Yellowstone letting one rip would come as a convenience. If I had the time, I’d travel to Yellowstone and drop a lit cigarette into Old Faithful if it meant the disappearance of my responsibilities into Earth’s mantle.

How strange it is to imagine a catastrophe on that scale. 3.7 billion years of work, eradicated in an instant. All systems and all species ground into cosmic dust, as everything was before a few proto-cells messed around with cyclical heat fluctuations and learned to duplicate. Think about this for too long and you’ll start asking questions. How did we get here, and why? What makes a human any different from an ant? We have bigger brains, I guess. But do we use them to derive meaning from our experiences, or to assign meaning to things in order to make our mysterious time here feel worthwhile? If everything lacks permanence, if it will all be destroyed by an asteroid or a volcano or Floridians, why care about anything at all? Why build a castle knowing it will fall?

I dunno. Something to do, I guess.

Despite all the unanswered questions surrounding humanity’s relationship with the universe, and despite how quickly we could be erased from it, I’m amazed that humans (myself include) manage to care about anything. We care about the ones closest to us. We care about the bodies given to us. We care about the trajectory of our lives and what we want to leave behind. We even care about pointless things, like football games and presidential elections. Whether we care because God exists or because that’s how biology convinces us to keep extending our genetic lineage, I also dunno. But thank goodness we do. Have you ever spoken to a nihilist? It’s like playing fetch with a dead dog.

Depression — general, seasonal, or the unfortunate combination of the two — has never stifled my ability to care. When the winter chill sets in and I become a loose pile of skin, I still very much give a shit about everything happening in my life. But, zapped of energy and willpower, I lose a chunk of my ability to act on what I care about, which makes caring much more painful. I care about my loved ones and my work and this Substack and all 80 of its subscribers (!!!), but fuck, I feel like I’m pregnant with a cinderblock, and the weight makes it difficult to do even the simplest tasks.

These two self-portraits by Rembrandt accurately depict how I feel during the warm months vs. the winter. In the first, our friend is in the literal summer of his life, drunk on youth and in love with his new bride, Saskia. Just a chummy guy drinking Stella Artois out of what looks like a laboratory beaker. I appear similarly after 6 p.m. on any day above 65 degrees.

The second painting shows us a man in the winter of his life. “He is an old man,” John Berger writes in Ways of Seeing. “All has gone except a sense of the question of existence, of existence as a question.” This is what I look like now, staring into a Google Doc and questioning the question of existence for a few likes on Twitter. I stare out the window and wish the trees outside still fluttered with leaves, believing a warm breeze and a little sunlight would lift me out of the metaphorical dumpster into which I have dived.

But that’s a bad thing to wish. If trees didn’t sever connection with their leaves at the end of autumn, they’d exhaust themselves and die. They’d deplete their energy stores within a few decades (a short time for a tree) and surrounding trees would outgrow them. Then they’d fail to capture sunlight, stop photosynthesizing, wither away, and become fungi food. That’s why even deciduous trees in warmer climates shed their greenery. Just like us, they need rest. They need time to take inventory, examine their environment, and decide where to grow and what to shed.

So, I’ve accepted this wintertime lull as a message from nature telling me to chill the hell out. I’ve directed my focus on a few tasks — things to work on, certain areas of my body to keep clean, etc. — and have stowed away the rest until the ground thaws. I could try to resist this message, as I have in the past (spoiler: made things worse), but giving a middle finger to nature isn’t wise. Neither is betting my chips on a global catastrophe to eradicate my duties. But in the event an asteroid does come crashing down, I hope I’m awake and near a window to watch it.

Things to Consume

A few items you may find enjoyable.

A book you should read

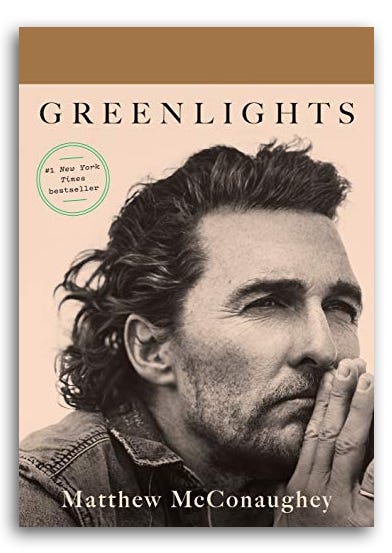

Greenlights by Matthew McConaughey

My dear Floridian friend and editor of Garbage, He Wrote — Rachel Earl (@sorbetoad) — and I read this together last month, just for kicks. In his first memoir, Mr. McConaughey recounts the story of his life and takes us through his spiritual journey, where he finds peace by listening to invisible forces and following his wet dreams.

Before reading, I expected it to be like any other celebrity memoir, peppered with self-indulgence and vague, unhelpful advice. Greenlights includes flashes of that, but McConaughey writes gracefully with enough awareness and criticism to offset any preachiness. Overall, this is a thoughtful and entertaining book that got even better when I started reading in his voice.

An album you should listen to

Lupin by Lupin

For his first solo project, the Hippo Campus frontman (Jake Luppen) stepped away from acoustics and made a moody and melodic 8-track EP. It has paired perfectly with seasonal depression.

An account you should follow

Managed by Utah State University libraries, this account posts old outdoor magazine covers. It is a dopamine drop to counterbalance the last 1500 words I’ve thrown at you.